HARTFORD BUSINESS JOURNAL

March 6, 2017 – By Gregory Seay

Cromwell factory owner Jack Carey saw the threat looming several years ago, and began steps to protect his product source, employees and the future of family-run Carey Manufacturing Inc.

Well before this sitting president’s “America First” campaign and mounting public support for boosting jobs at home, Carey, whose company supplies metal latches, catches and handles to commercial, industrial and military customers, sought to end its reliance on heavily subsidized Chinese raw materials and manufacturers of hardware found on everything from office desks to missile containers.

So by early 2018, Carey says his $8 million company will have invested $2.5 million in Connecticut-sourced laser cutters, a new quality-inspection station and up to eight new jobs, to produce in-house the more than 300 varieties of latches and handles listed in its catalog.

Chinese suppliers’ unpredictable pricing and uneven quality were Carey’s principal reasons for home-shoring his hardware production.

His move, one of Connecticut’s and the nation’s growing examples of the “reshoring” trend to bring certain manufacturing and technology back to America, offers plenty of benefits, including a secure, stable supply of product and more production overtime for his shop-floor workers, Carey says. But even more important, says Carey, is that America can recapture production of some obscure but vital components such as the metal missile-case fasteners Carey supplies to the U.S. military.

“We’re trying to compete in a world where … we’re competing against governments that give things away. It’s tough,” said Carey, a former Pratt & Whitney Co. machinist who launched his company in 1998.

According to industry observers, reshoring of manufacturing and related technology to America has been underway since the Great Recession but is still in its infancy. The trend dipped in 2015 due to the strong dollar and rising oil prices, which favored overseas production, according to the Reshoring Initiative, a Midwest nonprofit advocate of restoring well-paying manufacturing jobs and vital goods production to the U.S.

From 2010 to 2015, it’s estimated that Connecticut added 575 new jobs and eight new companies as a result of reshoring and foreign direct investment, according to the Reshoring Initiative.

Many of the jobs are coming back to America from Asia, particularly China, but Western Europe is also a major job-recruitment source.

Reshoring has gained momentum of late, Carey and experts say, due to relatively stable energy prices and an improving domestic economy that has triggered an upsurge in interest rates, spurring more American producers to act now to invest in new or upgraded capital equipment and facilities.

Another recent example is Hasbro Inc.’s decision to reshore by 2018 manufacturing of its popular Play-Doh, which hasn’t been made in the U.S. since 2004. The company plans to move some production of the moldable clay from China and Turkey to a facility in East Longmeadow, Mass.

In their 2017 annual survey of members, some of whom are in Connecticut, the Precision Metalforming Association and the National Tooling & Machining Association said one in four members reported that they reshored work in the past 12 months, up from one in five in 2016.

The chief reason members cited for reshoring work, both organizations said, was the ease of delivery, followed by quality control, and then cost.

“We’re going to be able to offer a high level of services to our customers,” said Paul Lavoie, head of Carey’s sales and marketing.

Engineer Harry Moser has spent 50 years in manufacturing sales, and founded the Reshoring Initiative (RI). In its previous manufacturer surveys, RI found that from 2000 to 2003, the average net number of producer jobs lost yearly overseas was around 220,000. By 2015, the number of jobs lost overseas was nearly neck-and-neck with reshored jobs, Moser said. The 2016 survey is not yet complete, but Moser said he expects it to show some small gains in net U.S. manufacturing employment. Connecticut’s manufacturing industry posted 1,000 new jobs in 2016, one of the first positive growth years the sector has experienced since the 1980s, according to the state Department of Labor.

“The reason we believe we can still do better,” he said, “is that we’ve gone from huge net [overseas manufacturing job] losses to positive job gains. … We have to substitute domestic production for imports.”

President Trump has made bringing back jobs to America a cornerstone of his administration, and he’s been critical of U.S. companies that have announced plans to move operations elsewhere.

One of the most high-profile examples was when he publicly criticized air conditioner manufacturer Carrier, a subsidiary of Farmington-based United Technologies Corp., for wanting to build a new plant in Mexico and move jobs there from Indiana.

Carrier eventually scaled back those offshoring plans, with the help of incentives from the state of Indiana.

Meantime, Trump and Republicans in Congress are working on a tax-reform package that aims to lower this country’s 35 percent corporate tax rate to make American companies more competitive in the world. There are also talks of a border-adjustment tax that would levy a 20 percent tax on all imports of goods and services into the U.S., further encouraging domestic production.

“We must create a level playing field for American companies and workers,” Trump said last week during his first speech to a joint session of Congress.

But reshoring is neither easy — nor cheap, Jack Carey says. First, there is the cost of equipment and technology needed to root production at home.

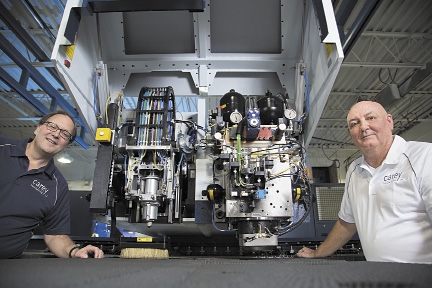

The tipping point for Carey’s reshoring decision was the demonstration of an automated laser-cutting machine tool from Trumpf Inc., the German toolmaker whose North American base is Farmington.

With an approximately 20-foot wide work deck, the $1.2 million laser cutter delivered in December is capable of multiple parts-shaping functions, including precise sheetmetal slices and bends. But like most automated machines, some trial-and-error is necessary by Carey’s engineers to fine-tune its nearly infinite number of movements. Carey also acquired two other Trumpf machine tools.

Burke Doar, a Trumpf senior vice president in Farmington, said Carey is but one of many customers throughout Connecticut and worldwide that in recent years have bought its machine tools to equip their own in-house production lines.

“Our tools are enabling Connecticut manufacturers to compete in a global marketplace,” Doar said.

Carey’s engineering staff, too, have the huge chore of redesigning every one of more than 300 parts in Carey’s catalog — parts currently produced in and supplied from China.

Jack Carey says expectations that reshoring will open up vast job opportunities for America’s un- and under-employed may be unrealistic. He says reshoring to Cromwell will add six to eight jobs, but also provides his existing 37 workers with continued overtime, a lucrative supplement to their base pay.

“It will create jobs,” he said of reshoring. “But nowhere to the level that we’d think.”

But Carey, who lives in Rocky Hill, says more than jobs are at stake from reshoring products and technology that were developed in America.

The nation’s defense, he said, increasingly relies on materials and components sourced from or made in China, this nation’s largest trading partner from whom America imports more than it exports.

“No commercial rivets are available in this country,” Carey said. “No one is tooled to make those products here. Everybody gave up production to Mexico and China.”